Surely there was more imminence in the second coming of Christ than in the acquisition of new Selden spreaders from the lower forty-eight. So, on Thursday morning I began shopping around town for a mend-and-make-do solution, opinions on which, I found, were as easy to come by as a cup of coffee in Seattle.

Mike Stockburger in the Homer Boat Yard office tapped the defective tubes with an index finger and thought awhile.

“Your boat been in high latitudes much?” he asked.

I explained she’d rarely been elsewhere.

“See that slight bulge around the cracking? I think water has got trapped in the spreader ends and froze.” Mike continued to ponder. “I think they’ll be OK though. It’s all compression load they get. No evidence of corrosion. I might not sail them into the Southern Ocean, but…” He could see I found this unsatisfying. “Or you might weld a patch over the top. Ask the guys at Bay Weld.”

Bay Weld has a vast workshop and up to six, aluminum fishing boats in build at any given time, but the foreman had no praise for the patch-weld solution. The welds would be strong, he said, but could weaken the surrounding extrusion. He recommended simply welding the crack closed, which would keep the metal failure from spreading but wouldn’t add back much in strength.

“I disagree,” said Walt, a welder building a 20 ton trailer behind Homer Boat Yard, a stone’s throw from Gjoa’s current berth. “Welding over the crack will pull the tube back together as the weld cools and contracts. That’s what I’d do.”

“Randall, we don’t usually weld anodized, extruded aluminum,” warned my friend Gerd, a metal boat builder and surveyor back home. “And your idea of wire wrap or hose clamps would be strong, but then you’ve got dissimilar metal issues. Ugly too. Only OK for a jury rig.”

Each successive bit of advice sounded as good and reasonable as the bit most previous, except that it was contradictory. And thus, Thursday ended without a clear way forward.

But overnight I had an idea and on Friday morning I stopped into Sloth Boats, a fiberglass boat building shop. “Yes,” said Eric Sloth, “Epoxy resins adhere very well to aluminum, and doing a full length wrap, a kind of splint, with heavy tape would add tremendous strength. Don’t quote me if your mast comes down mid Pacific, but I like the solution.”

Back at Homer Boat Yard, I floated this by Mike. “Probably unnecessary repair,” he said. “But sometimes a repair is meant to make us feel better. Do the fiberglassing by all means.”

_____

Homerians are a mend-and-make-do people. If you need it, you build it; if it breaks, you fix it. If you can’t do either, you move back to Anchorage.

But key to success is assessing how much improvement is in a given fix. In Alaska, getting good at this requires surviving some rather grand failures.

Mike Stockburger told this exemplary tale.

One spring, we flew the Piper Cub out to my cabin to do some hunting, just my buddy and me. Cabin’s in a valley on the other side of that range there (Mike waves towards the mountains across Kachemak Bay) and about 70 miles back.

I’d talked to the NOAA guys in town and thought I’d understood there’d only be a few inches of snow. The plane had those big, fat tires made for rough surface landings. I knew they could take some snow. But when I was making my approach, I realized, too late, that snow levels were more like two feet. I tried to drift the Cub in nice and easy, but it didn’t matter. The wheels dug in and tipped the plane over on her nose. Bent the ends of all three propeller blades to right angles.

Valley’s pretty deep, no radio signal, and no cell phone; didn’t have one anyway. We hiked the propeller up to the cabin and spent the next three days super-heating the wood stove, inserting the blades one at a time, and slowly pounding them back to shape with the blunt end of a hatchet. I got them pretty fair too. Tested them on the plane up to 2000 rpms, my foot jammed hard on the brake. Not too much vibration. Pretty proud of my work. I got my buddy in and taxied to the end of the valley.

Just then I heard a buzzing and saw a plane overhead. First plane I’d ever seen back there. Radioed up with my situation and the pilot said, ‘Under no circumstances should you take off with that prop. The heating can weaken the aluminum. If the straightened-tips fly apart at speed, which is likely, the imbalance will pull the engine right out of the plane. Happened to my nephew once. Once, god rest him. We only found a few pieces of his plane.’

I had the pilot call back to Homer; they flew out my spare prop next day.

_____

Generosity is another effect of Homer’s mend-and-make-do culture, and without giving it a second thought, Eric Sloth lent a corner of his shop to a total stranger for the weekend. By Monday I’d repaired the spreaders, and bolstered my confidence, for the price of materials.

Situated across from Northern Enterprises, Sloth Boats’ big shed can handle boats 70 feet in length and with masts 40 feet off the deck.

The shed allows work on big boats indoors. Here Sloth is just finishing up the addition of a tophouse to Star Wind.

Even tasks that take twice their anticipated time do eventually complete, and so Gjoa emerged from Homer Boat Yard’s Bay Five thirteen days after Mike Stockburger and team initiated their “four or five day job.” The delay had been inevitable; the quality of workmanship, high. I was pleased.

Already I had decided to leave Gjoa at Homer Boat Yard rather than truck her back to Northern Enterprises. Both are reputable businesses, but Northern is geared for the commercial fishing trade and provides fewer services to a clientele who need none but lift and splash.

The crew eased Gjoa into her space behind a shock of pines and then grabbed her mast from Northern for the two mile return trip. Finally the boat and appendages were all in one place, and I could set to the reconstruction. The rush was on. The goal, to launch in five days.

Problems arose immediately.

While installing the spreaders, I noted cracks in the aluminum extrusions near the bases. Two cracks, one on the lower leading edge and one on the lower trailing edge of the lower spreaders. The cracks were small, two and three inches, respectively, and in line with the extrusion.

The thought of sailing into the North Pacific with a flawed rig seemed out of the question. Thus, in an instant I had been gifted a new project.

This was Sunday.

The mast and rig are made by Selden, a large, highly regarded European company famous for its cutting-edge technology, attention to detail and record keeping. For example, each part of a Selden mast is stamped with a six digit number, and the mast itself is inscribed with its own unique identifier next to an inscription of the boat’s name, all of which gives one the impression that there is, somewhere, a vast warehouse with replacement parts awaiting just such a requirement as mine.

On Monday, I called the Selden dealer closest to Homer, a famous rigger in Port Townsend, Washington. A short conversation confirmed Selden’s reputation for detail.

“They are Swedish,” said the rigger. “Very Swedish, and they have a way of reminding you that you are not. But that’s not entirely bad when dealing in precision parts.”

I sent the requested information, part numbers, photographs, measurements of the spreaders, mast height, boat width, distance from mast base to lower spreaders, year installed, boat name, year built, contact information.

Nothing happened.

On Wednesday, I called. “Let’s see. Oh, yes. I haven’t been able to open your files,” said the rigger. “The photos say ‘will not download from server.’ Isn’t technology wonderful? Resend your spreaders and I’ll have a look.”

I resent the photos.

Nothing happened.

On Friday, I called. A woman answered the phone. “He’s traveling today,” she said. “Will be presenting at a boat show in California.”

“Did he leave any progress notes for me?” I asked.

“Is your name Bill?”

“No, it’s Randall.”

“No, no notes for Randall. Jerry?”

“Randall. Is he available?”

“Such a week. He’s been so very busy. I’m not sure when he sleeps. Are you asking me to call him?”

Something in her tone suggested I should pity the difficulties that attend upon those of genius. Would I seriously request she interrupt Mozart while he conducted The Marriage of Figaro simply to ask when he could get around to fixing my piano stool?

“I know my issue is a small one,” I said, “but I’m stuck. I’m beginning to get a little frustrated at…”

“Lit-tle fru-strated,” she said, scratching out a note.

“No, don’t tell him that!” I said, “He’ll never call if…”

“Ne-ver call,” she wrote.

“I mean, it’s just that it’s been all week and I don’t have any information. I’m trying to get this boat ready for…”

“Be-en we-ek al-ready.”

“Stop! I mean, I’m in a hurry too, right? It’s kind of upsetting not to have anything…”

“Ki-nd up-setting…OK…I’ll make sure he knows you’re upset. You have a lovely weekend.”

Monday. Nothing happened.

On Tuesday, I reached out to a famous Florida rigger. By afternoon I knew that replacement spreaders, in whole or in parts, were not sitting in stock in Sweden nor anywhere else. They’d have to be made to order. It might take two weeks. The Florida rigger would have a price quote by Thursday.

On Thursday, nothing happened.

On Friday, I called the Florida rigger. Selden needed until Monday to produce the quote, he reported. They’d be sending the spreader tube dies out to an extruder in Europe; all very complicated. Could run into some money. He’d call me back.

On Monday, nothing happened.

Given the rules regarding anticipation of project timelines, discussed above, I knew I needed an alternative solution if I wanted to depart Homer before Christmas…

I once read that the best way to budget for a boat project is to a) plan meticulously, and then, when all items are accounted for and you have your grand total, b) double it.

This technique applies equally to budgets of time and expense.

With that in mind, I dropped my jaw when Alida discussed her strategy. Alida is the proprietress of the house in which I rent a small, downstairs room while Gjoa is in the shed. A plummer by trade, she has worked on deep arctic oil rigs and major construction projects here on her native Kenai peninsula. She can as easily rebuild her car as her washing machine, when she’s not busy restoring her house and raising a family. Which is to say, she’s Alaskan.

While a contractor, she said, her approach was to add a ten percent buffer to a working budget.

Ten percent? I pushed back.

“Well, OK, on the building of this house things got out of control,” she confessed. “At one point I was three months behind on a three month plan and didn’t have the windows in when it started to snow. So, now I double the budget number and then add ten percent.”

This double-the-budget approach is so pervasive as to have achieved a state not unlike the law of gravity. Any more, it’s just assumed.

Examples:

When I informed Erin at Northern Enterprises Boat Yard that Mike over at Homer Boat Yard said Gjoa’s sandblasting and painting job would take about five days, he responded with, “So we’ll expect you back here in two weeks.”

When on day nine I told Carol, the office manager, that the work was looking to take at least twice as long as planned, her only remark was, “It’s a boat.”

When, after booking my rented room for three more days and then two more days and then through the end of next week, Alida took the long view by informing me I absolutely had to move out by the end of May. She was very firm about that.

And when Mike at Homer Boat Yard said the job would require about five days, what he meant and what I should have understood was something more like two weeks.

Now we are on day twelve of our five day sandblasting and painting project and, right on schedule, the last coat of anti-fouling paint is going on…

First coat of gray goes on. There will be two coats of gray for a total of four coats of primer sprayed over the bare aluminum. Having two colors serves as warning during future bottom projects and may help protect against aggressive sanding.

Oddly, the marketing pamphlet for E Paint SN-1 leads off with what this paint does not contain, that is, any copper. Copper, a biocide, is a standard anti-fouling paint component for many boats except those made of aluminum, which is so far below copper in its nobility that even with a good barrier coat, only the very self-confident would risk its application.

“Sure thing,” says Carol, “we don’t have tides this week anyway.”

Carol is the office manager at Northern Enterprises Boatyard, my home on the hard. I have just inquired if her crew would be available in the next few days to assist with pulling Gjoa’s mast.

Her response is jargon and translates as follows:

Tides in Homer’s shallow Kachemak Bay run to 20 feet, and when out, reveal a vast, gently sloping mud flat punctuated by the occasional boulder. No tide this week will entirely cover “the flats” or be anywhere near high enough to float any boats from the yard’s beach-side dock. For the purposes of lifting and launching here, where a typical low tide makes the crane and rampway look like a poorly conceived public works project, Northern is essentially shut down until the water comes back.

When tides are running high, the yard is constant activity, and there may be a line of boats awaiting a lift. If your boat is deep of draft, you may have only one or two such opportunities a month, and if your tide happens to be at 3 o’clock in the morning, Northern will be there to make it happen.

The purse seining fleet constitute the biggest boats around, and next to their double-high bridges and reaching net booms Gjoa looks small and ordinary. But these boats are designed to work in shallow waters; even though many are twice Gjoa’s size, they usually draw less than the six or more feet she requires.

For reference, Gjoa needs a 19 foot tide to float. The next tide with that range arrives on April 10th.

That’s my launch target.

March 23

Sandblasting has been underway since Monday and is slow work, reports Randy, the man in the white jumpsuit.

Each of my twice-daily visits to the shed finds him in just such get-up, swinging the blast nozzle as if watering a lawn. By now I’ve shaken Randy’s gloved hand and found his eyes behind the clear plastic shield, but I have no idea what he looks like beyond his height and general build.

Communication is challenging, too. Randy wears ear plugs as defense against a machine whose sound is that of 10,000 hissing snakes, and when he talks, his voice comes from deep within a protective mask and respirator surrounded by a protective hood.

Necessarily, conversations are short.

But the nub is this: Gjoa’s exterior hull appears to have been perfectly preserved by, if nothing else, an inordinate amount of high quality paint frequently applied. I think the muffled description was something like, “I’ve never seen so much effing paint.” The layers are upwards of 1/4 inch thick near the water line. And the epoxy is hard as a rock. All good news from my perspective, if not Randy’s.

The blaster being used is purposefully small. “More power would be nice,” says Randy, “but can get us into trouble. Paint’s the only thing I want coming off.” Even so, the job has been progressing at such a pace that he’s upgraded to a courser, more aggressive sand, which is green and whose consistency is that of the granulated stone used on asphalt roofs.

It’s noticeably heavier and has more bite, this new sand, when ricocheting off the face of an over-eager owner standing too close when the hopper fires up.

Note the nozzle size. The white that boarders the area of black is the primer; the black is anti-fouling paint. The surrounding gray is the boat’s bare aluminum hull whose dull, even finish now has the consistency of 100 grit sandpaper.

March 19

“Where you gonna put the rig?” asks Erin.

“The what?” I ask.

—

I’ve returned to Homer to ready Gjoa for a sandblasting and bottom painting job whose list of preparatory tasks unfamiliar to me, all of which must be completed in two days, extends to the floor. What started as a simple idea (Hey, let’s sandblast the hull while we’re in Homer) has become a cascade of complications.

Here’s the progression: the epoxy paint used on the hull will only cure in temperatures not usually found at this latitude until June. Thus, to complete the project in March means Gjoa must be trucked to a heated shed at the Homer Boatyard, a facility two miles from her current berth at Northern Enterprises. To fit into the shed, not to mention under the electric wires that cross the road in nine places, the boat must be below sixteen feet of height once aboard the flatbed trailer. To get her below sixteen feet of height requires removing Gjoa’s 62 foot tall mast and lowering the highly decorated electronics arch that sits on her stern rail.

That there is a crane large enough to pull the mast, a truck and flatbed long enough, and a qualified blaster with a heated shed whose prices are reasonable and schedule open, and all gathered up and ready at this end of town, is cause for amazement and nearly reason enough to make a start. The real reason for the work, however, is that both bottom and primer paints on Gjoa are tired, and the primer has worn away to bare metal at the foot of the keel.

But I digress. Back to the complications.

Pulling the mast requires removing the main sail and boom, disassembling the genoa furlers, dropping the genoa poles to the deck, removing the HAM radio tuner connection, pulling stuck cotter pins and loosening twelve turnbuckles of such heft that the wrench required for leverage can’t be held in place with one hand.

No task is difficult, but each comes with a twist for Gjoa’s new master, like having to learn the inner workings of a brand of furler unknown to me, or singlehandedly removing a mainsail from her mast cars, a job meant for two people, one of whom has the delicate touch of a brain surgeon, or risk spilling a near infinity of bearings onto the deck, over the side, and gone forever.

Lowering the electronics arch proves a special challenge, for though it is designed for just such an eventuality, the wires leading to its eight antennas are not always long enough to allow the descent without being disconnected, or worse, cut.

I am finished a scant two hours before Erin arrives with the crane, pleased at the thought that I can now sit back and let the yard crew hustle out the stick.

I fail to note as they approach that Erin and his rather diminutive crane are not accompanied by anything resembling crew.

“Where you gonna put the rig?” asks Erin.

“The what?” I ask.

“The rig, the line from the mast to that hook on the crane.”

It’s a brisk day. I’m in jacket, hat and gloves and am on the verge of shivering. Erin, a bear of a man, wears black overalls and a t-shirt.

“I thought I’d let you do that.” I say to his jest.

“Not me. I only supply the crane and the hook. Didn’t Mike explain? Yard policy says the owner supplies the rig, puts it on the mast, and attaches the rig to the hook.”

I say that Mike did not mention anything of the kind; that I’ve never rigged a mast to be pulled before—in the lower 48 I’m not allowed anywhere near that job–wouldn’t even know what line to use.

“Simple,” says Erin. “Most any line will do. Just put in a couple clove hitches on each end. You know how to tie a clove hitch, right? Heck, these masts don’t weigh anything. Two of us could pick it if it weren’t so tall. How you gonna get up there?”

I’m thinking hard now. No vision of this project has included my having to rig the mast, much less supervise the operation.

“You could lift me with the crane. I’ve got a boatswain’s chair,” I say, grasping at the first thing that comes to mind. This, at least, I have done before.

“No can do,” says Erin. “Yard policy says cranes don’t lift people. What about those little mast steps?”

“For emergencies,” I say. “I’m afraid of heights.”

“Me too. I’ll get the Snorkelift while you find a line.”

Suddenly this job is going sideways. Pull Gjoa’s great mast with a piece of spare line? I rummage up three such lines of varying size while Erin brings the lift around to Gjoa’s port side bow.

“That one’ll do,” says Erin, pointing to the smallest of the three I produce. “Last week I towed a car with a piece like that, and it only parted when I tried to pull a dozer. Dozer was stuck in the mud though.”

Up we go in the Snorkelift with me pointing hesitantly at a spot half way between Gjoa’s two sets of spreaders. Arriving there I straddle the basket, hooking a foot before leaning out, and commence to tie a rolling hitch, my improvement to Erin’s suggested clove. Over once, over twice, under and through. Not right. Try again. Over once, over twice, under and through. Not right. On the third try, I get it, but the rolls of the hitch are binding in the wrong direction. Start again. Nope. Again.

Bowline, half hitch, clove hitch, rolling hitch, reef knot. With these five a man can secure the world to its poles. I’ve tied each so often the tying is like spreading butter on toast. But this morning I am fifty feet off the ground, hanging none too securely from a Snorkelift basket, and engaging my boat’s mast in a hug that is still illegal in 27 states. A rolling hitch simply will not materialize from my efforts.

“Like this,” says Erin. I look over to see he’s tied a rolling hitch to the basket’s rail by way of instruction.

I resume, each attempt failing. Apparently, I don’t know how to tie the knot. Frankly, I realize, I don’t want to tie the knot because I don’t know what will happen next.

I climb back in the basket to take a breather.

“You pulled any masts before?” I ask by way of distracting Erin from my incompetence.

“Lots,” he says. “Once the owner had put the rig too low and when I lifted the mast it went end for end. The head dug a three foot hole in the ground as it swung and then the thing broke in half. This one’s lots bigger though.”

I sigh. Within minutes the line defending my idea of manageable risk from that of stupidity has dissolved. A mast in pieces is not a fair exchange for new hull paint. I’m not doing this.

“We have another option,” Erin finally interjects. Across the street is a rigging shop. I can have one of their guys rig the mast if you like.

“You’re just mentioning that now?”

“Well, they work mostly on fiberglass boats.” says Erin.

—

Next morning a man from Sloth Boatworks arrives carrying a proper mast strap (seat belt type material three inches wide and an inch thick). Within an hour Gjoa’s mast is laid gently on the ground. The flatbed arrives, and the boat heads to her temporary home in a heated shed and me to a rented room east of town.

The sandblast job has begun.

The strap in place and ready to lift. Note the very small space between masthead and end of crane boom. The crane is at full extension.

The lift begins. Note now there’s no space between masthead and crane boom end. We did not damage the mast or its aerials, but it was touch and go.

One casualty alone: the outer genoa furler drum caught on the rail as the mast went slowly skyward and was only noticed when it popped off with a bang. Rail bent. Drum bent very slightly but so far no noticeable defect to furler operations.

February 8

Homer weather changes every two hours and usually for the worse. So, if the sky clears, drop everything and do the outdoor tasks.

How often has a sunny morning encouraged me to begin work in the anchor locker that afternoon only to find that after lunch I am rained or sleeted or snowed into the cabin?

In a word, often.

By this time I’ve practiced all the archaeology upon the boat’s main cabin that I can. Every cupboard and locker has been emptied; every tool, spare part, emergency aid, length of rubber hose and clamp, engine belt, shackle, pin, toggle, and fastener has been sorted, photographed and cataloged. None of the boat’s interior spaces remains unexplored, save the vast anchor locker and stern lockers, which are only accessible from on deck.

Yesterday a deep, 964 mb low passed over (from the north and east!) blowing a gale in the yard. Gjoa rocked in her cradle, a contraption made of blocked up 2x4s that reminds disconcertingly of egg crates. Water sloshed in the sink; the boat vibrated as though she were housed inside a bass drum. Heavy snow fell.

Just after my 12 o’clock ham sandwich, the wind died and the sky cleared. I dashed forward and slammed open the anchor locker. But by the time I’d got the beast unloaded of its two large headsails in wet bags, four water jugs, a bucket of spare chain, a moving dolly, six fenders, three sets of oars, a near infinity of thick mooring line and an anchor remaindered from the Queen Mary, I could see a gray wall coming up the valley.

Within moments it was raining hard. This was followed in short order by sleet, then snowflakes the size of silver dollars. They felt like cool, wet kisses landing on my cheek. Slush began to build up in the locker. I had to retreat.

Next morning, rain and then sleet, but it cleared to blue sky by two in the afternoon, so I dashed again to the anchor locker and within an hour I’d emptied it and rolled 400 feet of anchor chain over the bow and down onto a tarp awaiting on the ground.

The whole point of this exercise, by the way, is simply to inspect those parts of the hull interior that can only be accessed from this locker.

No boat locker has yet been designed that allows the easy access of a human adult, and big as they are, Gjoa’s are no exception. Wide of mouth, the anchor locker quickly narrows as you descend such that entry is reminiscent of squeezing into a child-sized pair of lederhosen while performing a hand stand with a flashlight in one fist and a camera in the other and exhaling—only exhaling.

The hull interior below waterline and under where the chain sits looked in good shape. Full of water, as one would expect, but the interior paint down low was holding.

I attempted to remove the water with a pump I assumed for that purpose because it was in handy reach of my pretzelline, head-over-heals position. I eased it gently from its hook and, with some difficulty, maneuvered it into position with the hand that wasn’t holding on, one knee and a free elbow. I pushed the lever and got bubbles instead of suction, and in this way discovered the storage location of the pump I’ll, in some future month, use to inflate the rubber raft.

Extracting myself with care, I went below to warm up. But by the time I’d made coffee, it started to sleet, so I quickly reeled in the chain and threw down the locker lid. Then it started to snow. Then it rained.

When it cleared for the second time that day (what luck!) I dove into the port aft locker. Here is stored more mooring line, a gas generator, 100 feet of shore power cable, another bucket of chain, a Johnson Series Drogue that, in its bag, is the size and weight and rigor of a recently deceased linebacker; below this, a BBQ, a collection of rubber hoses, tins of epoxy in various colors, mounds of spare halyards and sheets and a large coil of standing rigging.

Once at the hull interior, I found some lifting paint, not surprising in a boat of Gjoa’s age, and enough of a concern to become a line item on the to do list when the boat is in a warmer climate.

—

Ran engine today for four hours. Batteries were down to 87% of charge, and though I should be able to take the charge down to 50% without harm, I just couldn’t stop myself. But as I looked up from checking the oil, I saw a man peering in at me through the cabin window.

Northern Enterprises Boatyard, my current home, contains some 300 vessels lined up like soldiers, only three of which, including Gjoa, are sailboats. I am not only the only person living aboard, I’m usually the only person here, except for the night watchman who ascends his tower at dusk and is gone by the time I wake. Thus, to see a face in my cabin window was unexpected.

For both of us, apparently.

“Who are you?” said the face.

“It’s my boat,” I said.

“But where’s that couple from Canada?” said the face.

“In Canada.” I said.

The face looked confused.

“I’ve bought the boat,” I said.

“When was that?” asked the face.

“Just now,” I said.

“Nice boat,” the face said, smiling, “You’re a sailor! I have a Joshua. Name’s Adam. Snow today.”

Invited below and over two cups of coffee I learned that Adam is another native Homerian, a fisherman by trade, a sailor at heart. He’s explored the east coast of Greenland in an old Colin Archer and wishes, above all, to freeze in for the winter far north of here. A self-avowed loaner but gregarious as all get-out, Adam knows every adventurer I’ve ever heard of, all of whom, it appears, have passed through Homer at one time or another. And generous to a fault. Soon I’d been offered the kinds of assistance I couldn’t have imagined the hour earlier—access to his shed and tools, introductions to every local welder and blaster. And that’s how I met Mike, who will take Gjoa into his shed next month and sandblast the bottom.

Insurance survey in the morning. Uneventful. Father and son team, both native Homerians. “Oh,” says the father when I ask, pausing as if struggling to remember, “Born and raised in Homer. Guess I’ve lived here all my life.”

Both men are soft spoken and polite but clearly excited to survey something other than a fishing boat.

They scrape the paint here and there; make special point to find the engine serial number, stamped to the underside of the block and closer to the bilge than bilge water, and note the charge in the fire extinguishers.

“You happy with the boat?” asks the father. “Very,” I say. “Good. That’s important.”

“Where you going?” asks the son.

They are bush pilots, I learn, and are eager to get to the airport on this clear day. Thus, within the hour they find Gjoa to be a stout workhorse of a boat with a cracked stanchion and an out-of-date life raft as the only noteworthy faults.

Once alone, I get to my first project, a domestic chore, putting heat shrink insulative film on the inside of the windows. Given the cold outside and warmth inside, all Gjoa’s windows have been dripping with condensation every time I’ve been aboard. This interior wetness makes below-decks seem clammy, and on my first evening, I couldn’t get the temperature above 64 degrees at the heater’s highest setting. Gjoa is warmed by a magic silver cylinder in the main salon, a giant Releks diesel heater that would do well on a much larger vessel. And while 64 degrees is quite warm enough, especially when outdoors is snowing and in the mid 20s, getting there shouldn’t take nearly so much fuel.

During the sunny part of the day I apply the double-sided tape around the window frames and then the film and shrink the whole affair with a blow drier I find in a head cupboard. That evening the cabin comes quickly to 65 degrees with the heater at but half throttle. Still too much fuel usage, but better.

Next task is to charge the batteries using the engine.

Though the four-battery house bank is at 91% of charge, I’m not sure when they’ve been charged last, and in any case I want to run the engine. Running the engine on the hard is possible because Gjoa has two large coolant tanks that are integral to the hull and are themselves cooled by the ambient seawater, or, in this case, air temperature (most modern boat engines pull raw seawater into the boat for this purpose, an odd strategy when you consider that a boat hull is designed to keep seawater out). The engine comes alive quickly, even though overnight temperatures have been as low as 26 degrees. That’s the good news. The bad news: it takes five hours of run-time to get very cold batteries back to 100% of charge.

The only disappointment of this exercise is that the exhaust put out more white smoke than I like, even when engine temperatures come up to normal ranges, 160 – 170 degrees. Likely all this means is that oil is escaping the rings and getting into the combustion chamber. The diesel is a 48 horsepower Bukh, built in Denmark for the lifeboat trade; she’s vintage 1988 and has 7,000 hours, which is to say she’s got plenty of life left, but is not a spring chicken.

Already I have formed my life-on-the-hard routine. Wake before sunrise. Make coffee. Descend the slippery ladder and walk the road in the crunch of ice and snow the ten minutes to the toilet; there I fill my two jugs of water from the tap (Gjoa’s water tanks are empty and will stay that way until it warms or we go back in the water). Back at the boat, make egg on toast, the blue flame of the stove and yellow yoke enough to cheer the soul of any winter morning, and sit for a time by the heater wondering how best to get to know this new creature, my boat, from her strange position on the beach.

Boats of a certain age have history, but not always a history as interesting as Gjoa’s. I’ve written previously about the two-year Northwest Passage just completed by Gjoa’s most recent owners, Ann and Glenn Bainbridge. It was on this passage and a waylay in Arctic Bay, Nunavut, that I first met them both.

The Bainbridges remained the winter in the Arctic. They put Gjoa on the hard in Cambridge Bay in the fall of 2014 and moved aboard a tug, Tandberg Polar, which they maintained until spring when the Norwegian crew returned, and then they, in Gjoa, continued on to Nome and eventually Homer.

For most boats that would be history enough. But not this boat.

Gjoa was built in Germany in 1989 for journalist, photographer, adventurer, Clark Stede, who, with Delius Klasing sailed then-named Asma around the Americas (west through the Northwest Passage, east about the Horn) between 1990 and 1993. Their book, Rund Amerika, is aboard, and is simply full of boat construction details, outfitting details, route details, weather details … all in German. I can’t read a word.

Here’s all I’ve been able to find online regarding Stede and the voyage in Asma.

Gjoa’s next owners were at least as adventurous, maybe more so. Tony and Coryn Gooch bought Asma in 1994, renamed her Taonui and took off. They had been cruising for a number of years in smaller, fiberglass boats, but were keen to explore the high latitudes, for whose demanding conditions a stronger vessel was needed. For 16 years they crisscrossed the globe every which way, sailing summers and putting Taonui on the hard in winter, such that a map of their travels looks like a game of cat’s cradle approaching its maturity.

One account of a passage to Antarctica.

In 2002, Tony set out from Victoria, BC to solo the globe via the southern ocean because, “I wanted to get down there one last time while I was still fit and healthy enough to handle hard sailing and enjoy it all.” He was in his sixties. Tony made the loop in 177 days. Distance: 24,000 miles. Average speed: 137 miles a day.

This brief history of Gjoa / Taonui / Asma may go some way to explaining my initial and continued attraction.

Specifications

Mako vertical windlass

1. 30kg S140 Spade anchor (primary)/120m G70 Certified 8mm hot dip galvanized chain with pear shaped end links

2. 33kg Bruce (secondary)/70m 16mm Liros Anchorplait/10m DIN766 chain,

3. Fortress FX-23 kedge

Whisper large-case, dual belt, 130 amp alternator on engine

Whisper house batteries, 4 x 145amphour Gel

separate start battery

Whisper Isolation transformer

Whisper 12v60amp battery charger

Whisper Sine wave inverter 12v/2000 watt

Whisper shore power

Battery monitor

Loncin portable generator

Standard Horizon Matrix GX2150 VHF with built-in AIS receiver (and handheld backups)

Standard Horizon CP590 GPS Chartplotter, 12″ display

Furuno radar

Echopilot Bronze forward looking sonar (and handheld depth backup)

Kenwood SSB/pactor modem

Iridium satellite phone

Simrad/Robertson HLD2000 electric/hydraulic autopilot that connects directly to the rudderstock.

em-trak B100 AIS transceiver

em-trak S100 AIS/VHF splitter

Inmarsat-c transceiver

Wind indicator

Epirb

- Wheel steering

- Hot water

- Pressure water

- Shower

- Refrigeration

- Solar or wind generation

- A painted hull

- Powered winches or sails

- Davits

- Deadlights in the hull

- Any instrumentation in the cockpit

- Watermaker

- Microwave

- A warm, dry doghouse to keep watch in

- Three watertight bulkheads

- Water tanks integral to hull create a double wall for puncture protection

- An aperture-protected prop

- Standpipes instead of through-hulls

Homer for the first time to see her sitting there on the hard like a bird awaiting spring. That was November. The snow fell wet and heavy and quickly turned to mud. Then back to San Francisco for a month of brooding. Then Homer again to buy her. And just like that The Figure 8 project has sprouted wings.

None too soon.

The process of procuring the Figure 8 vessel had drug its heels so long that its boots fell off and then it wore holes in its socks; its toes got frost bite and threatened to turn gangrenous, and still it drug on.

It was without humor that my wife said, “Watching you buy a boat is like water torture.”

Two years ago came the idea, and early on I was all excitement.

I found many boats with potential and more with the help of my sailor friends who forwarded listings.

Florida, Seattle, San Diego, Victoria, Grenada, Florida again; Cambridge Bay, and Port Townsend were just some of the places visited.

But none of the boats quite worked out. One was too small; another too big; another too old.

No need to be hasty, I told myself. The Figure 8 was a demanding course, and I was learning the requirements.

Obligingly, over time the requirements ballooned, and I found myself seeking a flush deck, pilot house, split rig, lifting keel, fat tanked, amply powered, speed demon with iron scantlings and insulation Eskimo approved … that I could afford.

I’d become Goldilocks, for whom no boat could be just right.

Two years of searching and so many boats nearly bought, commitments made and then retracted. I couldn’t tie the knot much less finish off with a round turn.

Finally I wondered if the boats I rejected were, in fact, deficient, or had I lost my courage?

Then Homer called.

Actually, Ann and Glenn Bainbridge called. They had completed their two-year Northwest Passage and were moving on to other projects. Their aluminum sloop, Gjoa, was available if I was interested.

I remember first seeing her anchored against the hills of Arctic Bay, Nunavut. This was early in the Northwest Passage I crewed aboard Arctic Tern. It was the summer of 2014. Now that was the boat, I thought. Except that she was taken. Except that she was happily plying to her purpose with a couple happy to be seeing her at it. I made an offer anyway. The Bainbridges smiled and declined.

I had no intention of waiting for this boat. But that is how it has worked out. Today, sitting snugged next to her diesel heater and typing this as a light, dry snow falls, I know that when the sky clears, I’ll go on deck and admire the white and craggy Kenai Range to the east and search again for wind on the waters of the bay. Because the Figure 8 project has wings.

At last year’s Strictly Sail Pacific Boat Show in Oakland, I found myself shooting the breeze with the guys at the Monitor Windvane booth when a gaffe overtook me. I try to stay ahead of thoughtless remarks by keeping my mouth shut, but even then I was talking about the Figure 8.

It was a natural-enough question that tripped me up: “What’s your strategy for handling the big winds and seas of the Southern Ocean by yourself?”

My unfortunate reply: “Down there is just more sailing. It’s the north that’s going to be difficult.”

Like many sailors, I’ve read endlessly of adventures below the great capes such that, in imagination, I’ve been there many times. But I’d not read the literature of polar explorers, not to mention the Arctic Pilot. I knew only that arctic routes were shoaly, icy, bitterly cold and infrequently passable. I’d get only one shot. It worried me.

Like most gaffes, my remark contained some truth. The Southern Ocean is, after all, sailing…if not just sailing. But what the remark failed to acknowledge was the difficulty of this sailing—managing a vessel, any vessel, in the kind of big winds and heavy seas that the south routinely offers-up.

So, it was with some gratitude, and trepidation, that I bumped into an article by Captain Eric Forsyth of Fiona by way of reminder that none of the legs of the Figure 8 can be thought of as just doable. Each will take careful preparation … and some luck.

Forsyth’s report is understated and matter-of-fact, and obscures that his experience includes 250,000 sea miles on Fiona.

—-

The following article comes from Ocean Navigator Magazine. More on Captain Eric Forsyth. More on his boat, the very stout Westsail 42.

Turned away

Aug 28, 2014

Gear failures sabotage a planned Antarctic circumnavigation

Eric Forsyth’s Westsail 42 Fiona nestled amongst other voyaging boats in Port Stanley, Falkland Islands.

Bob Bloyer

When I departed Long Island, N.Y., on July 5, 2013, I was making my fourth attempt to cruise Antarctica aboard Fiona, my well-traveled Westsail 42. My plan was ambitious: a westward-bound circumnavigation of the Antarctic continent.

I had successfully made it to Antarctica twice. On my one previous unsuccessful attempt I suffered a broken rib due to a knock-down just north of the Falkland Islands.

This Antarctic circumnavigation cruise did not start auspiciously: one crewmember did not show up in time for departure. I double-handed across the Atlantic from Long Island with the remaining crew, Wade. As we neared the Canaries, Wade learned his son was seriously ill and flew home from Tenerife. It was important that I stick to a schedule as the window for the Antarctic leg was only about eight weeks long, so I single-handed across the Atlantic to meet a cruising couple, John and Helena in Brazil who sailed with me as far as Santos. There I met David who had signed up for the Antarctic leg. We double-handed to Punta del Este, Uruguay, to pick up the remaining crew for the Antarctic, Simon and Bob. We refueled and loaded on tons of food before leaving for Port Stanley in the Falklands. There we prepared the boat for a crossing of the Scotia Sea: we installed deadlights on the main cabin windows, wooden cover on the aft hatch, double lashings on the rigid dinghy on the foredeck and we shipped a 65-pound fisherman’s anchor.

|

|

A 65-pound fisherman anchor was lashed to the bow pulpit for use in Antarctica. |

The forecast for the day we left was 30 knots from the west, which was okay as this would give us a beam reach. Our destination was King George Island in the South Shetland Islands, which lay almost due south of the Falklands. We left with the storm mainsail bent on, this is smaller than the working mainsail and has two reefs, the second being very deep, leaving almost a trysail when set. In Port William Sound before we encountered the offshore wind we tied in the first reef.

Pegging the wind needle

Offshore the wind was blowing hard with gusts to 50 knots, so we furled the jib and sailed with the reefed main and staysail. We tied the second reef in the mainsail. It was good timing; I watched with amazement and some trepidation as the anemometer climbed above 60 knots, the needle vibrating madly on the end-peg. That night we plowed south with shortened rig in rising seas. As the gloomy scene lightened with sunrise the wind dropped into the 30-knot range. The boat was taking a battering from huge waves. We shook out the second reef with foredeck gang wearing harnesses. The sea conditions were very rough.

I had just retired to my bunk in the aft cabin for a post lunch nap when Simon called out that the forward bilge pump wasn’t working and the head was flooding. I worked my way forward. There was a lot more water than just a stuck pump would account for. Even as we watched, the water level rose rapidly — we were sinking by the bow. By the time we had assembled a couple of pumps, the water was over the cabin sole. We got a bucket brigade going and I went into the water, sloshing around in the forward head to find the leak. A stream of water was running down the inside of the hull on the port side from somewhere behind a locker. The only thing up there, out of sight, was the gooseneck for the head, I shut the main thru-hull valve for the toilet and the stream slowed considerably.

.jpg?w=960) |

|

After departing Port Stanley, Forsyth and crew encountered heavy weather leading to a series of gear failures. At 53° S, 59° W, Forsyth made the decision to turn away from Antarctica and head for Cape Town. |

|

Alfred Wood/Ocean Navigator illustration |

When we got the water down to a manageable level I peered behind the panel in front of the gooseneck, the hose from the thru-hull valve was detached from the plastic “U,” almost certainly caused by excessive pressure as the huge waves slammed into the bow. Water had been pouring into the boat through an inch and a half hose open to the sea, I figure we were minutes away from sinking, or, at least, shipping enough water to cause a capsize. The problem in reassembling the gooseneck was that the white sanitary hose used in marine toilets hardens like steel when it is cold. To get the thing back together, David and I had to put the ends of the hose in boiling water to soften the plastic so it would slide over the barbs on the thru-hull valve and the U-fitting. Working in the pitching bow with sea water and the contents of the discharge hose sloshing about was tough and for the first time in more than 30 years was I seasick. Later we found the forward bilge pump was completely clogged by debris, which always happens when the water rises to new levels.

Interior soaked

The interior of the boat was saturated; besides the water splashing about from what was left in the bilge, the pounding seas found every crack in the caulking and forced water in. On the starboard side of the main cabin the pressure of the waves thudding on the sides forced the rubber gasket out from between the movable port and its frame. The result was that water gushed onto Simon’s bunk every time we hit a wave. All the other bunks were also soaked. As evening fell on the second day we retied the second reef in the mainsail in a wind that gusted to 45 knots. The wind slowly veered to the southwest and Fiona began to sail east of the rhumb line as she slogged to the south. After a few hours we gybed onto port tack and headed west, this produced a whole new set of leaks as the waves crashed against the port side. The navigation table was flooded and my laptop computer went the way of all flesh. Also, the inverter in the engine room failed along with many other victims of the flood. Two five-gallon jerry jugs filled with diesel disappeared from the aft deck.

|

|

To prepare for the expected heavy boarding seas of the Southern Ocean, the crew installed deadlights on the main cabin windows to protect them from breaking. |

In due course I decided we had sailed far enough to the west and asked Simon, who was on watch at the time, to gybe onto starboard tack. When Simon grabbed the wheel, which had been locked to the wind vane, he found it spun freely; the steering chain was broken! It is testimony to Fiona’s sailing ability that for some time she had been holding a good course in tremendous seas and strong winds without any rudder control.

A quick look under the pedestal revealed the failure; the master link fastening the chain which passes over the wheel sprocket to the wire rope leading to the quadrant had snapped under the tension needed to swing the rudder in the heavy seas we were enduring. Fitting a new master link took only a few moments and I noted in passing that there was only one other master link left in the spares kit. The problem was that the wire rope leading to the quadrant had come off the sheaves and the grooves in the quadrant, which was swinging violently as the rudder oscillated in the heavy seas. Getting the wire back was not going to be easy; the quadrant, which is a heavy bronze casting, fitted neatly in the quadrant box with little room to spare. With Bob helping, I lashed the quadrant to the end stop with rope and slipped my fingers between the quadrant and the sides of the box to get the wire back in the grooves. If the quadrant slipped its moorings to the stop I was going to be short a few digits. Bob guided the rope into sheaves under the aft cabin sole at the same time. Eventually we got everything in place and tightened up.

Appearing out of the gloom

As we went on deck to try the wheel, Simon gasped and pointed ahead; looming out of the gloom and spray were the rocky cliffs of lonely Beauchene Island only a couple of miles ahead, the most southerly outpost of the Falkland archipelago. We had got the steering fixed just in time to gybe over and head southeast again. The wind was 40 to 50 knots with occasional gusts that hit 60 knots.

|

|

Fiona’s rudder quadrant with tight clearances to the surrounding box. |

A few minutes later I was below when I heard violent sail flogging and Bob poked his head through the companionway hatch to say the staysail boom had broken! I rushed on deck to view a scene of devastation on the foredeck: shreds of Dacron lashed by the wind flew from the forestay and a port shroud. Bob and Simon struggled to get the staysail halyard down; the sail had split in half. When we got things a little more under control, it was possible to figure out what had happened; the swivel on the staysail outhaul block had sheared and the adjacent cleat had been wrenched out of the staysail boom. With this mess attached to the staysail clew, the sail had rapidly flogged itself to destruction. Although the boom had fallen to the deck it was not actually broken. I now faced a difficult situation; although I carried spares for the jib and mainsail, I did not have a second staysail. Without the staysail Fiona’s ability to sail to windward — particularly in winds of more than 25 to 30 knots when we weren’t using the jib — was seriously compromised. Most of the other failures already mentioned could be dealt with and Antarctica was still within reach, but the loss of the staysail forced a reappraisal of the cruise objectives. I knew there was nowhere nearby that could provide another sail. Probably Santos in Brazil was the best bet, but if we sailed to Santos there would be no time to head south again in the 2013/14 season, so Antarctica was out.

I was bitterly disappointed. The cruise had been in preparation for nearly a year, and, of course, David, Simon and Bob had signed up specifically to visit the Antarctic continent. Standing in the heaving cockpit with the spray flying in the howling wind, my heart was heavy; it looked like this was as close as we were going to get to Antarctica. I told the crew that I thought we had done our best, we had been very unlucky to run into weather like this and we had to consider how to get ourselves home in one piece. I felt our best strategy was to head to Cape Town, all the facilities were there that we needed — it was a long way, but it was downwind!

Turning away

Accordingly, at 53° south and 59° west we turned the boat around and headed northeast. Sometimes turning around when the destination is so close is the hardest decision one can make. The trip to Cape Town would be no picnic; it was about 3,500 nautical miles away, mostly sailed in the Furious Fifties and Roaring Forties. As it turned out, the decision was the smartest thing I could have done; we later discovered the main water tank had shifted in the melee and cracked; half the fresh water had leaked out. Later I compared notes with a crewmember of a cruise ship navigating the same area; he said they were hove-to with a wind of 75 knots.

|

|

Broken chainlink from Fiona’s steering system. |

During the next couple of days we rolled downwind, cleaned up the boat and tried to dry out our clothing and bedding. David rescued the hard drive from my flooded computer and pronounced the data could be retrieved. He managed to transfer the program used for SailMail to his own laptop so we again had limited e-mail capability, a major feat in the soggy, bouncing boat. One of the first e-mail messages I received was that the Antarctic pack ice was the farthest north it had been for 34 years, confirming that even if we had made it to the peninsula my original plan of an Antarctic circumnavigation would not have been feasible. The wind was variable and at times fell to 10 knots, but mostly the log mentions relative winds of 20 knots with swells rolling past the stern. I decided we would visit Tristan da Cunha Island, it was almost on the direct path to Cape Town. I had sailed there once before, 12 years earlier. I felt the crew would enjoy the chance to visit this isolated community. It was a leg of 2,000 nautical miles.

Second steering failure

Four days later, after enjoying typical 50s sailing, that is, frequent swells washing into the cockpit, what I dreaded occurred: the steering failed again. Fortunately the wind was in the 15-knot range and we hove-to under the reefed mainsail. On inspection I again found that wire rope was dangling from the quadrant and at first I just assumed the wire had stretched and dropped out of the grooves.

In order to keep the quadrant from shifting, we rigged the emergency tiller to the rudder post extension and Simon sat on deck holding the tiller over. Although the wind was not strong there was a heavy sea running and he had to work hard to hold the rudder in position. As Bob and I toiled in the aft cabin the boat rolled quite violently. Suddenly there was a bang like a gunshot and the quadrant crashed to the other side, fortunately our fingers were not in the way.

Simon was still holding the tiller in the original position; the substantial cast iron universal joint between the rudder post and the extension had fractured, this entirely due to the force of a wave hitting the rudder. As we had done on the previous failure, Bob and I tied the quadrant down with rope and finished repositioning the wire rope. When this was done it was obvious that the problem was not the wire stretching; something was broken. By this time we were all exhausted, the motion of the boat was fatiguing, night had fallen so we let Fiona lie hove-to while we ate a simple supper and caught some sleep.

|

|

The torn staysail stretched out on the dock at Cape Town. |

I lay in my bunk with dark thoughts; without the emergency tiller there was no way of steering the boat if we could not fix the original system. We were hundreds of miles from the nearest land — South Georgia Island — which was hardly a haven. I had no idea how we would steer if we could not fix the failure.

In the morning I discovered that the chain had broken inside the steering wheel pedestal; to get at it, the compass and engine controls had to be removed. We all gathered in the cockpit and carefully stored each part as I removed them so that they would not get lost in the pitching, rolling boat. We fished out the chain from the sprocket attached to the wheel and I removed the broken link using a grinder on the universally versatile Dremel tool. I inserted the last master link in the spares kit to join the chain together.

This was the last major failure, although I felt the sword of Damocles was hanging over us each time I saw the wheel working hard. Running down the 40s we had the usual minor problems; chafe of the Aries lines, whisker pole topping lift breaking, etc., but basically the boat held together and as we worked to the ENE the weather moderated and it got perceptively warmer.

Tristan da Cunha

Three weeks after leaving Port Stanley, the misty outline of Tristan da Cunha came into view. We had sailed about 2,500 nautical miles. There is a settlement on the north coast called Edinburgh, where a few hundred souls scratch a living by fishing. When we arrived the wind was quite light and we anchored, with some difficulty caused by thick beds of kelp, a few hundred yards off the shore. Being an open roadstead with no lee, it was rolly. The person on the marine radio told us we could not land as the place was shut down for a public holiday.

|

|

Eric Forsyth aboard Fiona following arrival in South Africa. |

The next day Simon, David and Bob dinghied over to the jetty while I stood by on Fiona. The harbor master assessed the conditions at the jetty and waved them away. So they returned to the boat, we put the inflatable away and upped anchor in a rising wind. Simon, on the bow, had to pull masses of kelp off the chain as it came up. We bore away for Cape Town, 1,500 miles to the east.

The weather north of 40° south was pleasant and we enjoyed wonderful sailing with favorable winds. Six days after leaving Tristan it was Christmas; out came our traditional tree and to no one’s surprise Santa Claus managed to leave us a few small presents. Cape Town was not far away and early on the morning of Jan. 2, 2014, the distinctive outline of Table Mountain welcomed us to South Africa. We had sailed 4,090 nautical miles from Port Stanley.

The weather after we left the Falklands was atrocious, and bore little resemblance to the forecast. It wasn’t the worst weather I have ever been in, but close. I felt particularly chagrined that I had exposed the crew to this rough treatment by Mother Nature when nothing in their previous sailing had prepared them for it. But they bore up wonderfully; David, Bob and Simon were great crew. As for myself, it is almost impossible to express the disappointment I felt when I made the prudent decision to turn away from Antarctica. When we swung Fiona’s heading to the northeast on that stormy night, I knew I might never get that way again, which some might consider a blessing. But for me it seemed like the end of a chapter of my cruising life.

————

Contributing editor Eric Forsyth has sailed his Westsail 42 Fiona nearly 250,000 miles, including two circumnavigations. He is a past winner of the CCA’s Blue Water Medal.

February 2016 Update. Murre has sold.

—

March 2015 Update

New Photos Added

Included in this repost of my November, 2014 description of Murre are a number of current interior and detail photographs. These shots were taken March 7, 2015 and can be found by scrolling to the bottom of this article.

November 18, 2014

This post announces that my current boat, referenced in a previous post, is for sale.

My tough cruising ketch and my sole companion for over 12,000 miles of Pacific Ocean passage-making, Murre, is for sale.

I bought Murre in 2001 and spent many summer weekends, and even some work nights, sailing her to the far corners of the San Francisco Bay. For years, the favorite activity of my wife and I was to high-tail it to Murre on a Friday evening and be anchored at Paradise Cove or China Camp before nightfall. In the winters I often put Murre in a covered berth where I slowly rebuilt and readied her for more challenging waters outside the Golden Gate.

In 2010 Murre and I took off. Over two years we made three long ocean passages; we explored Mexico’s Sea of Cortez, the tropical paradises of French Polynesia and Hawaii and even Alaska’s glaciers and the Inside Passage (map). Our course covered thousands of miles of open water; we passed through the trades three times and over the equator twice; survived calms and gales; saw seabirds and dolphins and flying fishes and the vast Pacific from 20 south latitude to nearly 60 degrees north. Without doubt it was the grandest adventure I could have imagined.

We returned under the Golden Gate late in 2012, and I’ve since been organizing the Figure 8 Voyage, a different kind of exploit requiring a much different boat.

So, my capable cruiser awaits her next departure with a new owner.

BASIC SPECIFICATIONS

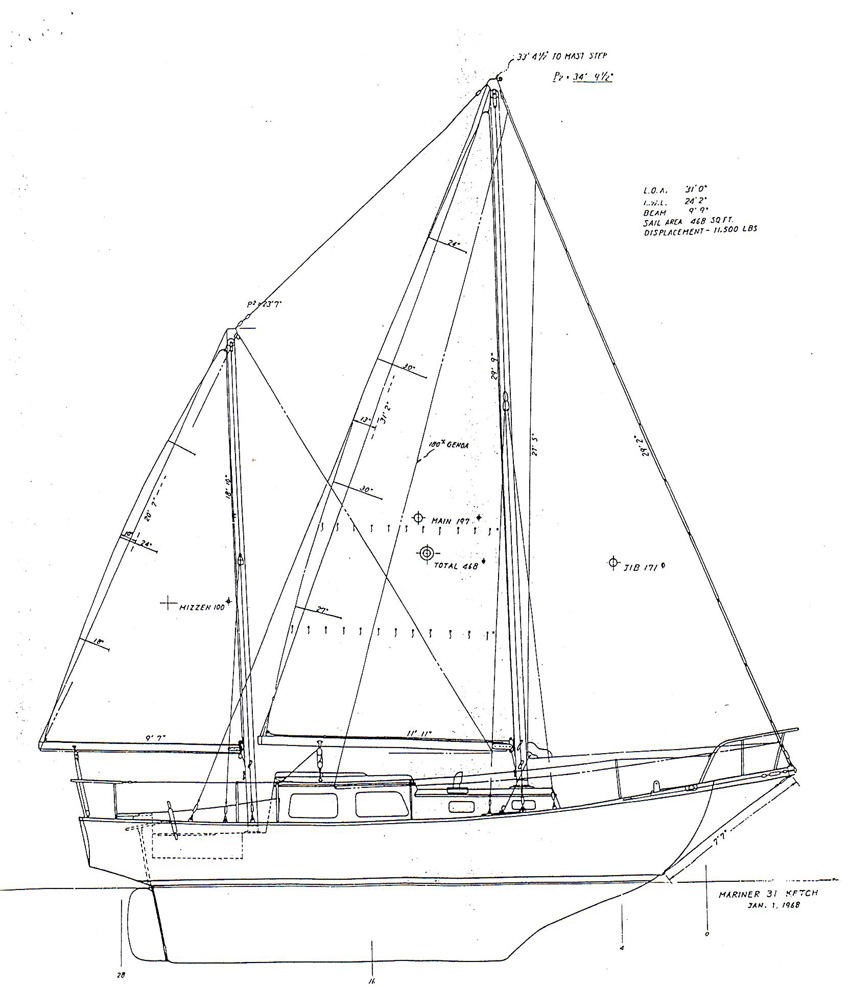

Murre is a Far East Mariner 31 built in Japan in 1972 and restored in California between 2003 and 2010. She is ketch rigged and has a full keel with cut-away forefoot and big, strong rudder controlled by a robust worm gear of bronze. Her hull is solid fiberglass, insulated between the deck and waterline, and her ballast is encapsulated. Her deck and cabin construction is glass and wood sandwich, replaced and heavily reinforced during the rebuild.

LOA: 31′ — LWL: 25′ 8″ — Beam: 9′ 9″ — Displacement: 11,500lbs — Ballast: 5,000lbs — Sail Area: 468 sq. ft.

Theoretical hull speed: 6.8 knots — Displacement to Length Ratio: 300 — Ballast to Displacement Ratio: 43% — Sail Area to Displacement Ratio: 13.97 — Capsize Ratio: 1.71 — Comfort Ratio: 32.51.

EQUIPMENT LIST

Engine: Perkins 4108 — 50hp; 70 amp alternator and new spare; Racor fuel filter; large Grocco bronze raw water strainer.

Tanks: Fuel, 40 gallons in one tank (plus 20 in Jerries in a locker); Water, 60 gallons in three tanks.

Electronics: Lowrance 7″ Chart Plotter (full Pacific chart cards) with HD Radar; Standard Horizon Matrix GX 2150 VHF Radio with AIS receiver; Hand Held VHF; ICOM M710 Single Sideband Radio with PTC III-USB Pactor Modem; Tactics wireless depth and knot meter.

Electrical: House Bank is 3 Group 31 AGMs of 315 amphrs; separate start battery. Banks are isolated by separate Blue Sea battery switches and combined for charging with a Blue Sea Automatic Charging Relay switch. Charging is via 70 amp engine alternator and 200 watts solar power in 4 panels.

Sails: Schafer roller furling system holds a 115% Hood jib; removeable inner stay for hank on storm jib; fully battened main and mizzen; mizzen staysail, mule sail, and “racing” spinnaker.

Dodger: Custom made companionway hatch cover and small dodger.

Rigging: Standing rigging beefed up and increased in size before passage making. Spinnaker pole customized for downwind cruising on headsail; removable inner forestay with running backs for storm jib; running backs for mizzen.

Galley: three burner propane stove and propane in two 20# tanks; single stainless steel sink with electric pump for fresh water and foot pumps for fresh and sea water; large ice box.

Lighting: LED cabin lights; LED running lights.

Heating: Force 10 Propane.

Steering: Edson bronze worm gear; Monitor wind vane; Raymarine tiller pilot

Ground Tackle: 35 lb CQR on the bow; small danforth as kedge on stern; 200 ft 5/16ths chain and 300 feet 1/2″ rode; manual windlass.

Emergency: Flares, ACR Aqualink PLB; Switlik 4 person life raft.

Tender: Inflatable “Avon”-type rowable.

Accommodations: Galley to port of companionway; small navigation station to starboard; two settee berths in main salon and fold-out dining table. Single head forward to starboard and hanging storage locker to port; large v-berth plus ample lockers both in the boat and in the cockpit.

CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF UPGRADES

2003 — Rebuilt and reinforced deck and cabin sides; stripped all bottom paint and applied barrier coat. Read about it.

2006 — Rebuilt cockpit well, massively reinforcing floors and mizzen support; replaced fuel tank with new. Read about it here and here.

2008 — Rebuilt aft cabin bulkhead. Read about it.

2009 — Fashioned and installed new bowsprit and spreaders. Read about it.

2010 — Replaced all stainless chainplates with new, nearly doubling thickness; replaced all standing rigging with new wire and turnbuckles and increased wire diameter by one size. Replaced all running rigging with new. Shot hull and decks with Awlgrip. Added Tactics knot and depth meter; Garmin chart plotter; Standard Horizon VHF and AIS; Icom M710 SSB and Pactor. Installed solar panels; new Blue Sea electrical switches; new Blue Sea battery switches; new Blue Sea ACR and volt meter. Installed Monitor windvane. Added new HOOD 115% headsail.

2011 — Replaced house bank with new 3 AGM 105s (Group 31) of 315 amphrs.

2012 — Added Lowrance 7″ Chart Plotter and HD Radar. Built custom hard dodger over companionway. Added Switlik 4 person liferaft.

RESOURCES: Mariner Owners website, Mariner Owners bulletin board.

MORE PHOTOS OF MURRE

Painting of Murre commissioned by my wife from artist and family friend, Nick Stewart. Not included in sale, not by a long shot. Contact me if you’d like to commission Nick for yourself or reach him at www.stewart2.com.

Icom M710 SSB Radio.

——–THE BELOW PHOTOGRAPHS OF MURRE WERE TAKEN ON MARCH 7, 2015.——–

Note Tactics wireless instruments for knot, depth, and compass heading; also, hatch boards have been reinforced with Lexan

Note standing rigging and chainplates are bright and clean. Both were replaced in late 2010. The standing rigging was bumped up one size and the chainplates were almost doubled in thickness.

Note vintage bronze and wood sheet blocks bronze rail. Also, cabin windows have been reinforced with Lexan.

Lowrance chartplotter is integrated with AIS in Standard Horizon VHF radio. Black triangles on screen are local AIS targets.

Large icebox is under green counter lid. Storage behind counter and stove extends down below the waterline–i.e. vast amounts of food storage for a boat of this size.

Anchor chain has been redirected into a large space below V-berth where there is room for the quantity one needs when cruising; this also moves the considerable weight of chain aft and down.

No one died. And yet, that time immediately after rejecting Steal Away felt like mourning.

During the survey, I spent the better part of five days discovering, thinking and planning aboard my new craft. I would eat here; I would sleep there; tools on that shelf. A dash to the mast for a reef would start by a grab at the rail here, my right foot there. Sit here to grind in the jib; there to adjust the main sheet. I’d begun to learn the boat and in so doing had grown attached. Vessel in hand, my imagination shifted; my mind moved to the Figure 8 course, wind, spray, an Albatross, that infinite undulation called ocean.

With the purchase, the project would finally manifest, the idea would have bones made of steel to hold its beating heart and onto which I could form the flesh. Now, and at last, there would be things that needed doing. Amen!

Without the purchase, all reverted again to the abstract, the hypothetical—pretty pictures and imperfectly rendered thoughts free floating in the Cloud.

Then my wife pointed to the tally of readers and friends who shared my disappointment. The sum came to exactly zero, the refrain, “wait for the right boat.”

The right boat! What on earth is that? Slocum did not choose Spray for her perfections; rather, she was free and could do the job. Likewise, Matt Rutherford’s St. Brendan, nearly as ancient as he and not much bigger, was all he could afford. At some point, said Phil Hogg in one of his emails, it’s more about the man than the boat.

In my ear Sir Ernest Shackleton’s whisper, “Go. Go now. To wait risks failure.”

—

Lately I have been reading Roland Huntford’s biography of Ernest Shackleton and have been amazed to discover that Sir Ernest, this intensely driven man of action, a hero by many measures and a giant among polar explorers, had a rather intuitive and haphazard approach to planning. For example, he never learned to ski, though Nansen and others had already demonstrated skiing’s advantages over traveling ice and snow on foot. Scott’s party, of which Shackleton was a member, made its first attempt at the South Pole with skis; that is, they carried them tied to the sledges that they man-hauled, and one could argue that Shackleton’s inept use of these skis on the long return—when he was ill, feeble and unable to walk—saved his life. Yet he did not incorporate skiing into either of his polar expeditions, a decision that probably cost him the prize.

Just so, dogs. Eskimo’s had been speeding over northern wastes with dog teams almost since the time of the first freeze, and Scott had sledge dogs in company, but none of the party knew how to drive them. Shackleton’s try at managing a dog team was a dismal failure and convinced him that dogs were not a polar solution. Instead Shackleton chose ponies, thinly furred, pointy-hooved animals, to pull the sledges on his first expedition, and the antarctic cold and crevices simply gobbled them up.

In stark contrast is Shackleton’s peer and competitor, Roald Amundsen, who studied the science of high latitude travel from a young age, poured immense amounts of energy into planning, and who bettered, with skis and dogs, Shackleton’s best, heroic efforts with an easy and dull efficiency.

—

So, when Sir Ernest swears to me that action is everything, I will quote him back with this:

“The … secret of [Roald Amundsen’s] success … was that … he acquired knowledge … and then bought his ship, instead of doing what most … explorers had done, bought the ship first and then acquired the requisite information.” (Shackleton, Roland Huntford, P. 159.)

Finding the right boat—that is, clearly defining scope, working through, in advance, the problems surely to be encountered, imagining every conceivable contingency—is at least as creative a part of this project as that which is to come.

The phone rang but once before Kevin, the broker, picked up. “Of course, no one is pleased with this decision,” he said.

Two trips to Florida, a Figure 8 boat found, offer accepted, deposit wired, a sloshy sea trial and a thorough survey. Then two days at home entirely at my desk, working and reworking the sums of those sheets I’d come to hate: “Cost to Departure” and “Refit Manhours.” A long meeting with the wife.

Then I declined to accept the boat.

Kevin was correct. No one was happy.

Steal Away, a Roberts Norfolk 43, presented well. A clean, flush-deck, full keel cutter with glossy topsides and a yacht-finish below, she was a simple, robustly-built and promising craft. What’s more, a famous (to me) sister ship had history in the Arctic.

In 2004/5, Phil Hogg and his partner, Liz Thompson, who run Fine Line Boat Plans & Designs from Australia, took their Roberts Norfolk Fine Tolerance through the Northwest Passage and had an exciting time of it. On the approach, a fishing net fouled their propellor and removal required lifting the transom from the water while at sea; ice blockages forced a retreat and an unplanned overwinter in Cambridge Bay, and then there was the below video of Fine Tolerance being towed through pack-ice by a Canadian Icebreaker. All of this the yacht survived, if not unscathed. (Phil and Liz tell their story here.)

I wrote to Phil an email bursting with questions. Would this Roberts I’d found be fast enough, capacious enough, seaworthy enough, and easily handled by one guy on a Figure 8? “Typing is not my strong point,” replied Phil before answering each of my queries in long and glorious detail. “We’ve 100,000 miles of cruising with Fine Tolerance much of it in the south. She’s a comfortable seaboat.”

This boosted my confidence in Steal Away, and Phil’s insights gave my learning of her a head start.

Basic Stats

Hull welded up in 1986 then shipped to Little Harbor Marine of Rhode Island where her interior was fitted. She was launched in 1998.

Steel, center cockpit cutter, hard chined, full keel, spade rudder, fully enclosed propellor.

LOA: 43; LWL: 37; Beam: 13; Draft: 6.9.

Displacement: 29,850 lbs (per design specs, but likely well over 30,000 lbs); Ballast: 9,000 lbs; Sail Area: 1082 square feet.

Displacement to Length Ratio: 242. Ballast to Displacement Ratio (after personal increment): 25%. Sail Area to Displacement Ratio: 18. Capsize Ratio: 1.78.

Sails: furling foresail, hank-on staysail; a Hood Stow-away furling main. Unused stormsail, trysail, and genekker.

Plating: keel, 1/4″; hull, 3/16″; deck, 10 gauge.

Insulation: Sprayed to the waterline between 1 1/2″ and 2 1/2″ thick depending on location.

Tankage: (to the best I could surmise) 100 gallons fuel, or a little less, in two mild steel tanks on either side of the engine room; 120 gallons water in two tanks in same locations. (For a time I thought there were two water tanks in the bilge.)

Engine: 56 hp Yanmar 4JH3E installed in 2000 (ratio of HP to designed displacement in tons, 3.6; assuming a more realistic weight of 17.5 tons/35,000 lbs, her ratio slips to just over 3).

Steering: wheel to quadrant.

Power: three 8D gel cells for about 640 in house amps.

Positives from the Figure 8 Perspective

- Steal Away was the best kept yacht I’ve inspected for the Figure 8, and it was evident that much care had gone into both her construction and subsequent maintenance. Her topsides, deck paint and stainless fittings sparkled as did freshly painted bilges and an eat-in engine room. Below, first-class interior joinery was matched by a seagoing system of stainless latches for both cupboards and floorboards. Wiring ran with professional orderliness into her electrical cabinet and flowed into purpose-built raceways when moving fore or aft. Even her odd, built-for-two layout had been well conceived.

- Her uncluttered flush deck allowed for an easy dash to the mast, and a deep, narrow cockpit would be a safe center from which to singlehand.

- A small companionway hatch, an entire lack of deck or cockpit lockers (inconvenient) and few opening ports added to her safety and meant she would be dry below, even in extreme conditions.

- Her hull was robustly built and a full keel that held the propellor captive added safety when in the company of ice.

- Living spaces were conveniently amidships. Dropping down the companionway put one in the galley with a navigation station just forward and a sea berth just aft.

- Hood Stowaway to one side, there was a simplicity, even minimalism, to Steal Away’s design and layout that appealed to me.

Original line drawing of the Norfolk 43. Steal Away differs from the above in that she has a redesigned and enlarged rudder for better downwind tracking and (somehow) a 37 foot waterline as opposed to the 32 foot waterline in the drawing.

Long starboard-side bench under which are the fuel and water tanks (same on port), one easily made into a sea berth, the other a shop.

Engine room amidships and under cockpit. Easily accessible from port or starboard and clean as a whistle.

Chain locker forward. Though well aft of the bow (a plus), the tube does not allow enough space below it for the chain to pile without fouling the tube. Would need to be modified for solo work.

The main bilge. Note the valve and water pump to the right attached to what appears to be a tank integral to the hull. In fact, THIS IS THE HULL; the valve is intake for the refrigeration coolant system. This mistake on my part was a big setback and contributed to my eventually declining the boat.

Why I Haven’t Bought Steal Away

Steal Away’s attractive simplicity indicated, in part, her intended service area–the tropics. She lacked a hard dodger, a heater, hefty ground tackle; her roller furling main was unfit (hats off to Dodge Morgan) for serious ocean work; her numerous solar panels would need augmenting with a generator. Though long, the list of upgrades was not daunting and most were indicated by a careful review of the broker’s photos even before the initial inspection.

But two things caught me off guard during the survey and sea trial. On my first visit I’d found the main fuel and water tanks opposite the engine room. Though their actual capacity was unknown to the current owner, some quick measuring suggested they held 120 gallons of water and 100 gallons of fuel. My fuel capacity goal for the Figure 8 is 250 gallons in tanks, so I was happy to discover what appeared to be two, large, in-hull water tanks lining the bilge. Having these would allow me to convert the other water tanks to fuel and put me very near the fuel tankage target.

However, upon inspection during survey, these “tanks” turned out to be … the hull! The plumbing that exited the tank to port and which I had supposed filled with freshwater intended for the galley actually transported seawater to the refrigeration cooling system. I was agog at my miscalculation, and much of the day’s remainder was spent measuring the boat’s bilge spaces for extra tankage (sadly, there wasn’t much).

The second gotcha was engine power. In the Fort Lauderdale canals Steal Away came up to near hull speed, but only after a time, and she backed down with the stateliness of a ship. For any cruising grounds other than those I intend, this would hardly be considered a problem. However, given Arctic conditions, Steal Away would have to be run at expensively high RPMs much of the time with precious little in reserve for making way in ice or headwinds.

Neither of these discoveries alone was the end of the world. Since this summer’s Northwest Passage on Arctic Tern, I’ve retreated from the Figure 8 as a “non-stop” endeavor. Without the need to depart San Francisco with all fuel aboard, I could carry jerry cans on deck. And I could repower. Steal Away’s Yanmar was both immaculate and on the new side. Her resale price would be high.

But these new costs, when added to the expected others, led to a big number. More importantly, they added significantly to the preparation timeline. Suddenly the Figure 8 boat would not be ready for her shakedown cruise until late July. And how much could I learn about sailing my vessel in those six weeks prior to a September first departure? The more I refined my estimates, the less they made sense.